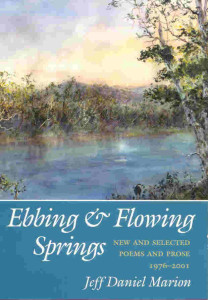

New and Selected Poems and Prose, 1976-2001

New and Selected Poems and Prose, 1976-2001

by Jeff Daniel Marion

Ebbing & Flowing Springs, Danny Marion’s seventh full-length collection, is truly special in that it draws from the author’s work over the period 1976-2001. The collection includes twenty new poems and, perhaps of greatest significance to his large and loyal following, previously uncollected stories and essays. Ebbing & Flowing Springs was named the 2003 Appalachian Writers Association Book of the Year.

Jeff Daniel Marion’s moving collection of poems, short fiction, and prose, spanning over thirty years of writing.

0-9658950-3-3

240 pages, cloth edition

(hardcover) $25.00

Ebbing & Flowing Springs

Author

Author

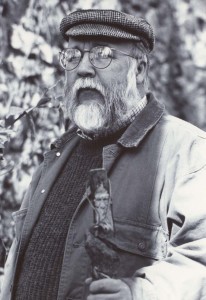

As poet, teacher, editor, printer, and lecturer, Jeff Daniel Marion has helped to create and support the literature of the southern Appalachian region over the last three decades. His poems have appeared in more than 60 journals and anthologies. His fiction has appeared in The Journal of Kentucky Studies, Now & Then and Appalachian Heritage.

In 1978 he received the first literary fellowship from the Tennessee Arts Commission. Marion was honored at the 1994 annual literary festival at Emory & Henry College. In 1996 he delivered the Palmer memorial lecture at Cumberland College and was named the Copenhaver Scholar-in-Residence at Roanoke College in 1998.

Marion grew up in Rogersville, Tennessee, and retired in 2002 after thirty-five years of teaching at Carson Newman College. Although his official residence is in Knoxville, Marion’s inspiration often comes while reflecting on life in his writing retreat overlooking the Holston River. Marion’s work is testament to an enduring truth: “Some springs never run dry”

Reviews

“For twenty-five years Jeff Daniel Marion has eschewed poetic fashion and poetic posturing, going his own way, making poems that are confident enough to speak quietly to us, even gently. Yet to call these poems modest is a mistake, for in poem after poem Marion achieves a depth and profundity only the most talented and ambitious writers achieve. That this depth and profundity are also found in his prose writings adds to his accomplishment. It is my hope this book will give a writer long recognized as one of Appalachia’s best writers the national recognition he deserves.”-Ron Rash

“The scale and depth of Jeff Daniel Marion’s achievement are now evident. In Ebbing & Flowing Springs we can celebrate the richness and wisdom of his work. His voice in poetry, fiction, and nonfiction is one of our most authentic, and one of our most beloved, by readers old and new.”-Robert Morgan

“The secret title of all good poems,” Galway Kinnell once said, “could be ‘tenderness.'” He could easily have been speaking of Jeff Daniel Marion’s new and selected poems and prose, Ebbing & Flowing Springs. In the midst of an ever-passing, ever-present natural world, Marion honors in crafted, vivid language the child, the father, the mother-even the Buddha of the cornfield and a faithful old dog. No experience, however slight it may seem, passes this poet’s attentive eye. Read this book for its aesthetics, its nostalgia, its wisdom, and especially for its tenderness.”-Cathy Smith Bowers

Excerpts

LOOKING BACK, LOOKING FORWARD

My mother loved to tell the story of when I stood at the grave of Daniel Marion, my great-grandfather, and asked, “Mama, is that my grave?” I couldn’t have been more than six or seven at the time and I wish that I could tell you I remember precisely what I was thinking. But I can’t-what I have is that little story, an often-repeated fragment of my past told by an observer intent on shaping, molding, and nurturing my life. What I can tell you now from the vantagepoint of having lived more than half a century since that day is that this story still haunts me, continues to startle with its truth.

Could it be that in some deeply intuitive way far beyond the rational powers of a six-year-old, I felt a connection with this man, this ancestor dead some twenty-five years before my birth? Of course, I bore his name, simple reason enough to feel connected, to believe our fates were intertwined, maybe even one and the same.

The first Daniel Marion was a cobbler and cabinetmaker, a skilled craftsman, someone we would call “good with his hands.” He made things to last, a fact I can attest to because I have the cupboard he made from cherry and walnut. I have studied his craftsmanship, noted the wooden pegs carefully carved and fitted to join planed and hand-oiled boards. Smooth and gleaming, tight, durable, and sound-this piece of furniture has endured into the fourth generation, serviceable but also beautiful. To the eye of an appraising antique dealer, the piece would probably be worth hundreds of dollars. But its value to me lies in another realm-call it a spiritual presence, an eloquent voice from the past. The truth it speaks is of the profoundly human need to create, not only what is functional and useful, but also something whose form adds grace, a pleasing harmony of line and color.

The cupboard’s very existence is also eloquent testimony of the man who created it, who chose the wood, split and sawed it, cured it, then painstakingly shaped it piece by piece, plank and dowel, shelf and drawer, dovetail joints all by hand. All this for necessity, yes, but also for love-of a woman, the care of family, and a thing well made.

This summer as I prepared to move my great-grandfather’s cupboard from my uncle’s house to my kitchen, I removed the wooden peg handle from its slot, being careful with the doors and their wavy panes of glass. What startled me was the newness of the wood on that peg handle, as though it had been tightly fitted into its slot only days ago by a skilled hand who probably whittled it to fit with his pocket knife. I felt its smoothness and smelled the wood, its aroma still fresh. The handle had perhaps never been removed from its slot since the day my great-grandfather first fitted it into the door. And now here it was in my hands. What rushed back to me in that moment was the memory of a day several years ago when my father, my son, and I stood at my great-grandfather’s grave, a late summer’s day visit to the old homeplace off Slate Hill Road in Mooresburg. We stood silently looking down at the simple lettering of his tombstone: Daniel Marion. These three-Jeff Daniel Marion, Jeff Daniel Marion, Jr., and Stephen Daniel Marion-studying what’s in a name, each deep in his own thoughts, borne on the currents of time, washed ceaselessly back and forth.

I have a photograph of Daniel Marion, the great-grandfather whom I never met but whose work I so admire. And, yes, with his white beard, expressive eyes, and wrinkled brow, we bear a striking resemblance. Even though several family members have commented on the physical similarities, it is in another realm that I feel most deeply my kinship with him: I too aspire to make a worthy and durable thing out of the words I choose and pare, whittling details to their essence, seeking the grace of a harmonious line, the curve where thought and feeling merge. Indeed, my work grows out of necessity, the need to create, to say and shape my life, the need to work at a craft that can give lasting body to the love I feel for my world fast fading and too soon gone. The grave marker ever reminds me to live fully, love deeply, and work hard, for the night is coming.

As a worker in words whose gift comes partly from that long-ago worker in wood, I offer these writings, testimonies to a place and time deep in the heart’s core. And surely it would not be surprising if this great-grandson of a worker in wood told you that, long before he ever saw his great-grandfather’s cupboard, the first word he learned to spell-taught to him through the tedium of a summer’s day by his Grandmother Marion-was the word cupboard.

EBBING & FLOWING SPRING

Coming back you almost

Expect to find the dipper

gourd hung there by the latch.

Matilda always kept it hidden

inside the white-washed shed,

now a springhouse of the cool

darkness & two rusting milk cans.

“Dip and drink,” she’d say,

“It’s best when the water is rising.”

A coldness slowly cradled

in the mottled gourd.

Hourly some secret clock

spilled its time in water,

rising momentarily only

to ebb back into trickle.

You waited while

Matilda’s stories flowed back,

seeds & seasons, names & signs,

almanac of all her days.

How her great-great-grandfather

claimed this land, gift

of a Cherokee chief

who called it “spring of many risings.”

Moons & years & generations

& now Matilda alone.

You listen.

It’s a quiet beginning

but before you know it

the water’s up & around you

flowing by.

You reach for the dipper

that’s gone, then

remember to use your hands

as a cup for the cold

that aches & lingers.

This is what you have come for.

Drink.

A LETTER TO MY GRANDDAUGHTER; ALLISON FRANKLIN

Remember the day you came to my house by the river-you were barely two years old and after taking a quick look around, you exclaimed, “Water everywhere!” We all laughed-your mother, you, and I-at the mud puddles in the driveway, the stream in the drainage ditch, the droplets falling from the trees, the Holston River sweeping by. Yes, water everywhere.

Standing here at the turn of the century, what can I tell you, dear heart? That the river is a voice, but it does not tell its secrets easily? Your great-great-grandfathers were rivermen, rafting their logs on spring tides down river to the D. M. Rose Lumber Company in Knoxville, riding home on the Peavine Railroad, their winter’s labor tucked in their front overalls pocket as greenbacks. And you great-grandfather taught me to fish this river, nurtured my adventurous soul by spending days helping me and my buddies build a raft so we could float down past Malinda’s Ferry and around Horseshoe Bend, past the fish traps an early tribe of Native Americans made, camp for a night or two along the banks, believing we were discovering a new country. I still have an arrowhead I found on that trip along the banks of the Holston. Someday you will hold it in your hands and know the wonder I felt when I first found it, feel the connections with a life lived ages and ages ago, but still alive in your hands.

So it is that the river gives up its secrets. I have spent my life listening to it, first as that boy who loved to go exploring its banks, watching as men brought great baskets of mussels from the river, selling the shells and marveling at the twisted pearls within. Once I saw a man carrying a huge fish, its paddlebill unlike anything I had ever seen, its body as long as the man. And one day on an early spring fishing trip with your great-grandfather, I slipped and fell into the water. He did not say a word, did not scold me, but quietly went about gathering driftwood and built a fire to warm and dry me. I can still smell the sweetness of that smoke from nearly fifty years ago.

It was your great-great-grandmothers and your great-grandmothers who told me stories of preparing the meals for the men who would go onto the river, their days of standing over wood cookstoves, packing baskets with fried chicken, cornbread, pots of beans, and pies. Secretly they said prayers to bring their men home safe, for the river in those days was no easy beast of burden. It could be wild, its currents unpredictable, its rages deadly. But those women did their work, sent their men off prepared, waited, and hoped for their return.

And what returned were stories passed on to me by your great-great-grandmothers, your great-grandmothers, their sisters and brothers. Yes, the river is a voice, and I’ve listened and coaxed its stories forth. So I offer you, dear one, the only river I know-of life into words, of words into stories, of stories that are our lifeblood, the flow of time past into the present. Remember and love and cherish the river. It is our past and our

future. Let there always be water everywhere.