by James B. Johnston

by James B. Johnston

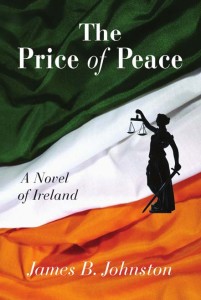

Gráinne O’Connor is a widow in her forties. Her search for justice leads to her arrest and a trial in which the key witness for the prosecution is the man responsible for the murder of her husband and son.

For a nation weary of death and destruction, the 1998 Belfast Peace Agreement signals the end of thirty years of conflict in Northern Ireland. But victims of The Troubles soon realize there’s a price to pay – the early release from prison of the very people who made them victims. For Gráinne O’Connor, this price is too high. As she searches for justice, she forms an alliance that ultimately leads to her arrest. Her subsequent trial for murder sets the stage for the novel riveting examination of justice.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=obFoG84KW5Y

$25

The Price of Peace

ebook: 9780989138086

$14.99

The Price of Peace – ebook

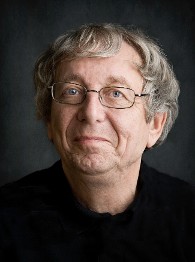

Author

James B. Johnston was born in Belfast, Northern Ireland and educated at Grosvenor High, Belfast, and Trinity College, Dublin. He immigrated to Canada in 1974 and moved to the United States in 1984.

He currently resides in Knoxville, Tennessee with his wife, Ann. The Price of Peace is Johnston’s debut novel. His collection of poems, Exile: Poems of an Irish Immigrant, was published in 1997 and has been reissued in a revised and expanded edition, Exile Revisited (ISBN: 9780984783618).

Reviews

The first comprehensive review of The Price of Peace and Exile Revisited is in the July 2012 issue of Rapid River Arts & Culture Magazine. To access the review, click on this link: http://issuu.com/rapidrivermagazine/docs/07-rriver_july2012/16?mode=window&viewMode=singlePage&backgroundColor=%2322222

Excerpts

It is no coincidence that the first quote I use in this book comes from Senator Mitchell. This is because the novel, although fiction, has its roots in the Northern Ireland peace process. Just like the Middle East peace process, the Northern Ireland process was fraught with significant challenges that threatened at any moment to derail the talks. For many months, it was two steps forward and one back. But unlike the Middle East process to date, the talks in Northern Ireland produced the 1998 Peace Agreement, an agreement that for the last fourteen years has allowed the people of Northern Ireland to live in a semblance of normality and begin healing. It is not an understatement to say that Senator Mitchell’s perseverance was pivotal to the achievement of the successful outcome.

This story is not, in any way, meant to take away from the importance of the Peace Agreement and the enhanced quality of life experienced by the people of Northern Ireland subsequent to the Agreement. But it tries to show that even peace has a price, a price that raises significant questions about justice, and the relationship of justice to peace and forgiveness in the lives of the individual. I hope these questions will resonate with readers regardless of where they live, for justice and personal peace have universal application.

I was born a Protestant in East Belfast. My wife was born a Catholic in North Belfast. Both of us lost close friends in the civil unrest; some killed in bombings, some in shootings. When we left Ireland for North America in 1974, we could not foresee an end to the Troubles, so the 1998 Agreement was a milestone event. But as I read the terms of the Agreement, my heart ached for the families of victims of the Troubles. In July 2000, all of the prisoners sentenced for terrorist crimes would be released. For some of these families, this had to be the hardest day of the peace process.

Almost without exception, when faced with the death and injuries of loved ones, families would plead that there be no retaliation. But, almost without exception, those families sought closure through their faith in the justice system. Even when they were able to forgive, they expected the perpetrators of violence to be brought to justice.

As I read the reactions of victim families to the early release of prisoners, my thoughts increasingly focused on the meaning of justice. A father who lost his son described the releases as an affront to his son’s memory. “These people can walk away from prison, walk away from their sentences. We can never leave our sentence behind.” A woman orphaned in a bombing said she felt let down and the victim of another injustice.

I began to ask if there is such a thing as justice. If so, what is it? I wondered whether justice is for the living or for the dead, and out of such thoughts, The Price of Peace was born.

On one level, the novel is simply a work of fiction; a legal thriller that pits prosecution and defense in a chess match with an uncertain outcome and the risk of a stalemate. But on a deeper level, my hope is that the story will encourage the reader to think about the meaning of justice. Is justice merely the punishment for breaking a law? Or is it more akin to acceptable, legalized, revenge? How critical is justice to a family’s process of closure? What are the relationships between justice, personal peace, and forgiveness?

There are a myriad of potential answers to these questions and throughout history they have been the subject of legal, philosophical, and theological debate. But, when I think of justice, two characteristics predominate: one is fairness, the other is equity. In the novel, I believe that is all Gráinne asked for.