by Arthur J. Stewart

by Arthur J. Stewart

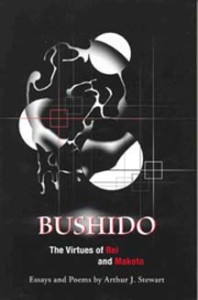

This second collection of essays and poems by Arthur Stewart has a single theme – respect and care for life.

Whether addressing cultural differences in Ghana, care of an Appalachian stream or increasing concerns of global warming, Stewart illustrates the importance of two of the seven Bushido virtues – Rei and Makoto – respect for the earth and its diversified and sometimes disparate cultures and establishing honesty through the pursuit of truth and pushing back the sense of disorder. He does this not only with the seriousness of a scientist but also with a vivid sense of humor, continually challenging the reader to change the lens and experience a new perspective.

0-9658950-6-8

96 pages, soft cover

$15.00

Bushido

Author

Author

Arthur Stewart is an ecologist, senior scientist, essayist and poet. He graduated from Northern Arizona University, and then spent two years as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Ghana. Upon returning to the U.S., he earned his Ph.D. at Michigan State University, then completed a postdoctoral fellowship at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. He taught aquatic ecology and conducted stream-ecology research as an assistant professor at the University of Oklahoma, then returned to Oak Ridge National Laboratory to work as an aquatic ecologist and ecotoxicologist. He has authored or co-authored more than sixty articles and book chapters and has served as editor or associate editor for Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, Journal of the North American Benthological Society, and Ecotoxicology. He is currently adjunct research professor at the University of Tennessee, and lives in Lenoir City. Stewart’s first collection of poems, Rough Ascension and Other Poems of Science was published in 2003.

Reviews

“A profoundly original concept, steeped in traditional wisdom, this gorgeous volume is life-enhancing — something to take us soaring; something to hold onto while we re-experience space, earth, sky.”

— Marilyn Kallet, author of Circe, After Hours

Excerpts

Ghanaian Story

Kwami

Growling bear of a black man, Kwami swings

his massive head left and right, bright eyes

buried in a coarse face, gaze searing the underbrush: he has

the perverse will of a hungry man in a desperate place.

Huge buttressed trees he hacks and girdles to bring down

a little burst of light-patch. Lianas, pulled, slashed

by machete, thick as an arm are oozing: they get dragged and stacked.

They smolder; a crackle of wet smoke crawls from the tangle.

Things grow

practically as fast as he can cut. I stand sweating just watching him

ripping a gardening place by the home. His wife is growing

a confabulation of yams: their soft green tendrils

creep up bamboo poles, minor hope

blasted dark each afternoon. He wants to grow

maize, okra and tomatoes but the huge trees

near the garden’s edge are too dominant.

Today clouds take all morning

pushing up, lusty white

mushrooms of energy: later the drops

come huge and fall slow. They hang

suspended as they fall, each

drop is its own thing, coming

suddenly together in a rushing roar: binding

to one another, joining

the sounds of drops, mingling —

they speak in many little voices. In the rain for a moment

Kwami just stands there, breathing, listening.

After the rain: the murmur of children,

the smoke of lianas lingering. And always

the yams, pallid masses dug from the thin red dirt in season,

steamed or boiled or baked, or stewed or souped. He, Kwami,

still standing, but now

in the doorway of the dark hut,

rattled loose to thunder, looking out

past roof-thatch, past the papaya tree, into the forest,

into the afternoon made dark luminescent

by rain receding.

The fish call with no voice

After the rain I walk to the edge of a pond a short way

into the forest: the fish call

somehow with no voice. I see them slipping

pale as yams, back and forth

in the water like smoke. The pond

is dark and motionless: it is

holding its breath; it seems pinned

to the forest floor by the lilies, thick at the edge.

A bird calls, then quiet. My heart lurches like a blind thing,

though glancing back towards Kwami’s hut I can see

rooftop: rare rain-free

afternoon sun glinting

from the clearing. The only sound

this instant, somewhere,

trickling water.

Then

more sound, motion. Four children chattering,

from Kwami’s house; naked but for tattered shorts

come towards the pond to watch: their voices

like birdcalls, a vine winding nowhere. In the pond

the fish move

just under the water; they seem to be counting

the slow strokes of their fins;

they are coming

like children

now through the stems of the lilies, towards me, opening

and closing their mouths,

staring —

I do not know how they know

but they move

closer, their mouths, the light

and shadows working together

in the luminescent world of green and black, the fish

silver, in silence. They come to me and I, mindless

god of do-good then

plunge the arm and grab one by the gill-cover and jerk

the heavy body to the light, up

flopping hard bankside, silver on shadow,

sides heaving, red gills gripping

solidly at empty air, the mouth

opening and closing now my heart

lunging in time to the bird-call

chattering of children

arriving, excited.

Pride spills through me like an uprush of rain backwards: food,

beyond the pale of yam, cheap rice,

onions and lean black beans, the wet fish

still thrashing weakly.

Trophy home

Hooking fingers under gill-cover the wetness

bleeds down my hand; I swing the timeless symbol of trophy-catch;

I feel pure, slimed joyful to bird-call perfection.

A thing is wrong and set to right

Kwami lunges from the dark of hut-house reeking of palm wine, eyes

wide blazing, clarion face a storm of disbelief stumbling anger, staring

at the fish

hanging from my hand: the dead soul

of an ancestor: his father’s father, his mother’s mother, or older brother,

or brother of brother, maybe; he reeks and rants, the bird-calls

of the motley children gone,

the sun

slamming now hard bars of light,

the words crash the high trees, the clouds

still pushing up away; his woman

bent hoeing yam hills straightens, tightens her cloth, stands silent

yet things

still green in the silver shadows.

I am emptied completely. We talk

for a long time that afternoon, settling until fireflies

work together at dusk, punctuating the calls of the new night

with small

speckles of hope. It takes two big calabashes of fresh palm wine

and a full

bottle of Schnapps to right the wrong and the fish

we bury at last, drunk,

staggering to the yam field

together, machetes swinging dangerously digging random holes in

darkness.